︎︎︎A SHOUT IN THE STREET

1 to 31 july 2021

As the first residency of the Espacio de Todo, we invited the artist and mediator Elena Blesa Cábez (ESP)* to carry out this research for a month, who worked with the environment of Vallecas and its slogans.

The following is a text written by the resident that tells the story of the work process, accompanied by images of the work.

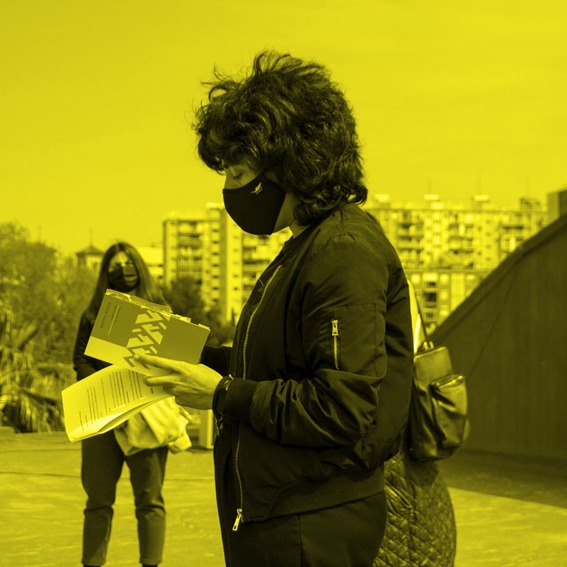

Photography by Antonio R. Montesinos for the project "En Potencia - l'Hopitalet".

Through shouts, proclamations and slogans, the residents on the streets have expressed their demands and claims in relation to the neighbourhood, but what has happened between Vallecas nuestro (Our Vallecas) -1976- and the current demands of associations, residents and collectives?

In this research we set out to think about how language, both oral and written, has been used in relation to the construction of the social and political imaginary of Vallecas. We wanted to review which voices currently make up the discourses present in the public space, connecting them with the historical imaginary of the neighbourhood, in order to trace what modifications there have been in their updating.

As a starting point we decided to analyse the proclamations used by the historical neighbourhood movements in Vallecas. In post-war Madrid, a number of neighbourhood associations emerged with the aim of demanding an improvement in their living conditions. The seed of the neighbourhood movement and other associations in the neighbourhood was the precariousness of the housing in the suburbs that originated as a consequence of the rapid internal immigration of Spaniards to Madrid.

Neighbourhood demands were aimed at getting the administrations to invest in improving basic elements such as street lighting or sewage systems in their neighbourhoods, although it is not possible to start from the premise of the existence of a single cause to explain a historical phenomenon as complex as the emergence of these movements and associations. The historian Marc Suanes explains that a social movement is a system of narratives, a system of cultural records of its time, a set of explanations of how certain social conflicts are expressed socially(01). It is precisely this narrativity of the social movement, its capacity for self-explanation, that interested us in this project.

With the end of the dictatorship, many of the endemic problems that already existed in Vallecas and many other neighbourhoods continued to drag on. After Franco's death, the Municipal Management of Urbanism drew up three Partial Plans - territorially limited urban development plans - that affected Vallecas and aimed to manage its urban development problems. In these new Partial Plans, the expulsion of the population was proposed for the benefit of large landowners. At that moment, a new neighbourhood counter-offensive began, which reached its peak in a demonstration in June 1976. It was a time of "crisis of representation, crisis of the old revolutionary projects and forms of organisation. In short, a panorama marked by uncertainty, but also by the emergence of new forms of life, of new experiential aggregations, of unprecedented forms of political mobilisation, of themes that take up the power of the 'no', based on social self-organisation"(02).

From the end of the 1960s onwards, these neighbourhood struggles were articulated by the recently created Neighbourhood Associations. In fact, the Palomeras Bajas association was the first to be set up in 1968, taking advantage of an associative formula that the Franco regime had established for other purposes(03).

In the 1976 demonstration, some 25,000 people marched through the neighbourhood chanting "Vallecas Nuestro" (Our Vallecas). This event became part of the historical heritage of the Vallecas neighbourhood movement. As anthropologist Elízabeth Lorenzi explains in her book Vallekas puerto de mar. Fiesta, identidad de barrio y movimientos sociales (Vallekas sea port. Party, neighborhood identity and social movements) a year later another decisive event took place, an agreement by which the Ministry of Housing delimited the area for the execution of the three partial plans, the land where the 12,000 families affected would be rehoused, and which also decreed the expropriation of the land of the large landowners. The achievement of so many struggles is beginning to be glimpsed"(04).

There is a question that runs through this project: what has happened between Vallecas Nuestro (Our Vallecas) (1976) and the current demands of associations, neighbours and collectives? Social movements are very diverse, but in a rather simplistic way we could differentiate between classic and current social movements. The classic movements would include the labour movement, the trade union movement and neighbourhood associations which, with the arrival of democracy and the welfare state, underwent a process of institutionalisation in which many of their members ended up forming part of official political parties. The new social movements are generally more assembly-based and reject institutionalisation. They propose citizen participation to achieve their mobilising force and their structure tends to be more decentralised and organic, which sometimes makes their continuity over time difficult(05).

Images of the research process, from the archive of Sergio Cabrera.

This brief introduction serves to situate the first phase of the project, in which, in parallel to the review of archival textual and photographic material provided by Sergio Cabrera and complemented by a visit to the Anarchivo (Anarchive) of the Espacio de Todo (Space of All), we met to talk with several people linked to various social movements, both neighbourhood and other types of associations.

From the 1960s to the present day, all kinds of slogans have been launched in a multitude of mobilisations. Many of them became paintings(06), stickers, posters or other material that has generated an informal archive in which one can detect many of the demands that have crossed these movements and the evolution they have undergone. Shouts and slogans such as "We want our rights and we want them now", "Right to a roof over our heads" or "Our parents emigrated, not us, housing here and now" are present. This trail can also be followed through the memory of those people and associations involved in these processes who agreed to talk to us over the summer.

From these meetings we generated a map of agents or entities that we understand to be connected in some way with the neighbourhood movements that emerged from the sixties onwards and their struggles. These struggles were not only based on the demand for decent housing and public facilities, but also included feminist and anti-fascist associations. It is interesting to note how, from various associations and spaces such as La Villana de Vallekas(07) -a self-managed social centre that brings together various collectives, such as PAH Vallecas, Orgullo Vallekano or the Escuela de las Periferias- there is a certain tendency to rescue a historical narrative that reproduces a stereotypical narrative in relation to Vallecas, leaving aside many other elements that could enrich and diversify it. At present, it is being reproduced in a way that does not fit in with social reality. The emergence of other narratives is being demanded by various collectives, such as Orgullo Vallekano, which are committed to breaking with the discursive, gestural and visual imagery traditionally associated with the associative left and to generating propositional discourses. These new ways of doing things put social rights, autonomy and collective care at the centre, breaking with traditional ideological positions. This could be one of the main differences with the Neighbourhood Associations that still survive today.

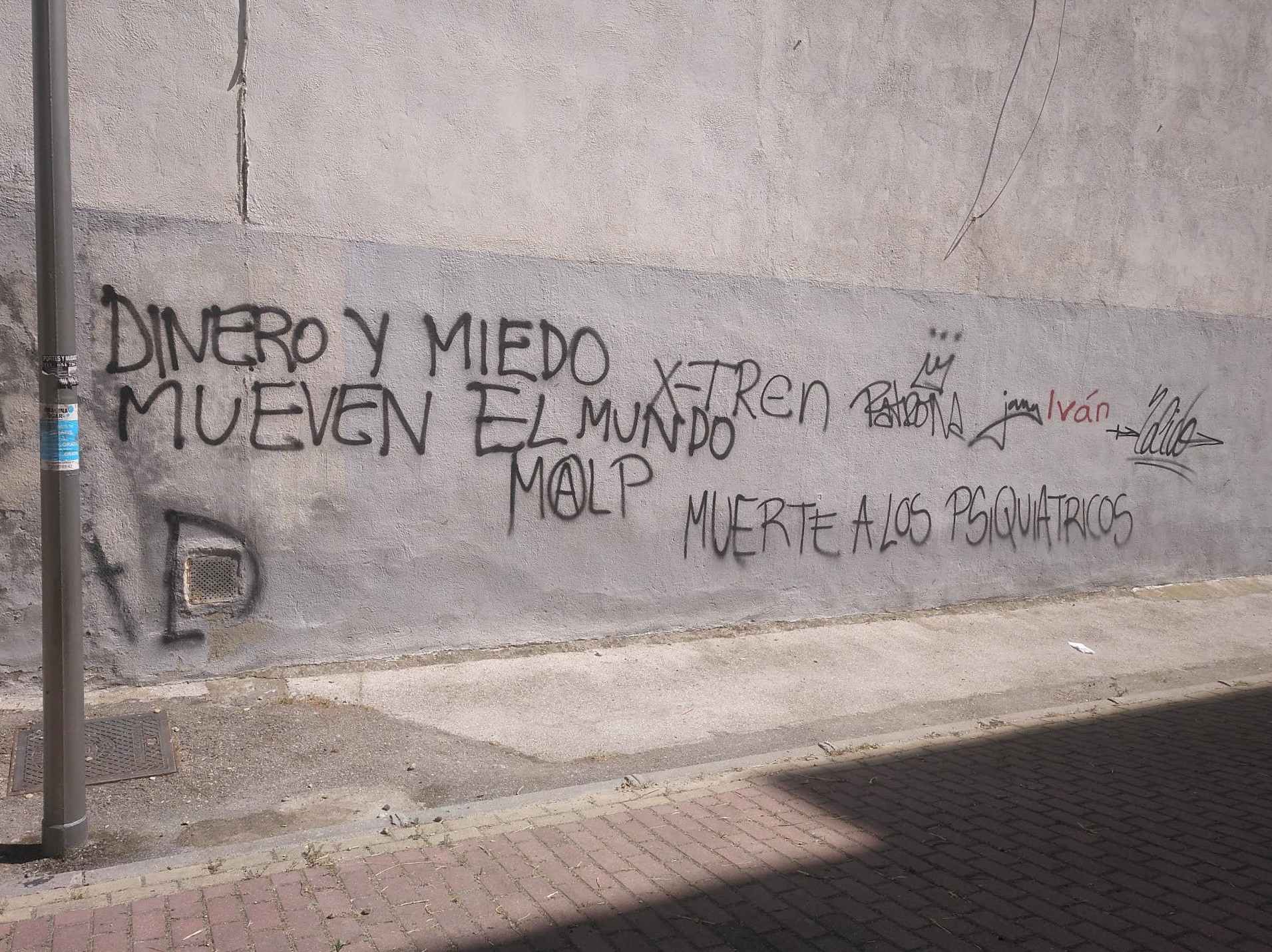

This part of the research was complemented with a series of routes through different parts of the neighbourhood where we detected a greater presence of this type of proclamations in the public space. During these walks, we photographed them, whether they were posters, paintings, stickers, T-shirts, etc. From these photographs, we systematised all the information by writing all the text on a large mural that we then used during the workshop as a reference. In addition to organising the material by zones and themes, and making visible those words that were recurrently repeated, this emptying served to free the message of any visual burden. Within the social movements, certain highly connoted aesthetics have been generated - through the use of certain typographies, colours, compositions... -. They are visuals positioned on a political level, even more than the textual content itself, which can sometimes be very empty and ambiguous, for example: "government resign", "power is people" or "fight and resist". Fight against what? who is resisting?

We also visited some of the spaces that the new collectives have tried to recover, claiming a territory with its own identifiable characteristics and not only defining itself as otherness or periphery. Through the creation of new spaces and traditions, the aim is to generate a new identity narrative, a new imaginary that revives a sense of community that has been disappearing in recent years with the processes of gentrification and displacement suffered in some of the neighbourhoods of Vallecas.

Images of the workshop held at the Espacio de Todo.

In order to open up the research to those neighbours who are not part of any collective or association, we convened a workshop on 22 July 2021 at the Espacio de Todo (Space of All) to collectively investigate the uses of language in public space. In a two-hour session, we will try to analyse the displacements and updates of different discourses and demands of a local nature, relating them to previously selected archival material. We invited each participant to bring to the session those slogans, cries, proclamations that they had seen or heard in the streets and that had generated interest. Thus, we proposed to work around the following themes: housing, public/common policies, feminist and LGTBIQ+ movement and anti/fascism. The selection of these themes was neither casual nor capricious; they allow us to trace a genealogy of these demands from the 1970s, when initiatives such as the Teatro de barrio obrero described their proposal in this way:

In the beginning it was necessity that created, back in the early 70s, the movement. We were against Franco. We demanded our daily problems as workers: the right to decent housing, the right to a sexual culture, the right to be people, against exploitation, against misery - in short, you know all about that situation(08).

This connection can also be read in the streets of Vallecas today, where, during walks, we find slogans such as: "They are not nostalgic, they are Nazis" or "Pride. Freedom to be"(09). While it is true that there are ideological lines that are maintained, some of them clash in their approaches. Those who decide to write "Ayuso bitch" when they could write "Ayuso resign" are not exactly in line with those who feel the need to write "macho, question your privilege", although a priori we could classify them all as left-wing proclamations.

Register of slogans found in street drifts.

The workshop was conceived as an open discussion through which to detect what changes there have been in the vocabulary present on walls and walls. New concepts and struggles that historically had no presence appear: transphobia, gentrification, social emergency, trans law, machista, ableism, eviction... Although some, such as the notion of neighbourhood or working class, are still very present.

In addition to reviewing the historical archive and the archive of graffiti and street texts that was generated during the month of residence, we stopped to analyse El barrio es nuestro (The neighbourhood is ours), a project carried out by the Todo por la Praxis collective in 2012. This project was based on research with the collaboration of the Federación de Asociaciones de Vecinos de Madrid (FRAVM) in relation to neighbourhood movements through the compilation and revision of photographs of the different mobilisations carried out since the seventies. So the proposal of Un grito en la calle (A shout in the street) could be read as a sort of update of the exercise carried out by the collective almost ten years earlier.

Most of the first neighbourhood demands were for improved facilities and neighbourhood development. For this reason, El barrio es nuestro (The neighbourhood is ours) was chosen as the guiding thread of this project(10). This slogan sought to synthesise the spirit and slogans used in the various mobilisations to demand improvements in social services, public facilities and neighbourhood development(11).

For the 2012 project, the chosen slogan was articulated in different formats. In addition to the reproduction of this slogan on canvases, posters and stickers, a large "corporeal poster" - as the collective has called it - was built, which has become part of the public sculpture park in Palomeras Bajas.

I take the liberty of taking a brief look at this piece because, in one way or another, it has become part of the Vallecan imagination on many levels, both institutionally and personally. But that does not stop it from raising questions, questions that are not new. On the one hand, Daniel Villegas already reflected in 2012 on this piece and its affirmation: "Whose neighbourhood is it? From where is this assertion made? What is the context in which it is inserted? how does it become visible? These are some of the questions that appear when these words take shape"(12).

For this analysis, the left-wing and militant past of most of the inhabitants of the neighbourhood since the 1940s was once again used as a reference point. This stance is justified by a visible neglect on the part of municipal policy makers, although this is precisely what has also fuelled it.

This district was the only one in Madrid that resisted the hegemony of the right, or at least it had been until the elections to the Madrid Assembly in 2021, in which the Partido Popular (People’s Party - PP) was also the most voted force in the electoral districts of Puente-Vallecas and Villa-Vallecas(13).

Register of slogans found in street drifts.

With this political shift to the right hovering over our workshop, the phase of analysis and reflection led to this question: is it possible to update a slogan like "The neighbourhood is ours"? While some of the lines of action of social movements - such as the struggle for housing, public policies or more recently common, feminist and LGTBIQ+ movements or anti-fascist struggles - are still valid, who is the subject of these demands? Is there still a us capable of channelling community demands and desires? This "Vallecas is ours" or "The neighbourhood is ours" is based on a collective mode of enunciation. Under our, we sense a us that leads us to think of a collective desire that moves the community. Historically, a Vallekan political subject had developed, closely linked to a type of homogeneous left-wing militancy that has been fractured in recent years with the appearance in the public sphere of identity discourses that for years had been silenced by the hegemonic political discourses.

Thus, to close this research, we proposed a collective action, a subtle infiltration of the public space - a space that is increasingly legislated and controlled, increasingly impersonal and with less and less trace of these struggles in the streets - through which we invite reflection on the Vallekano imaginary. Faced with the impossibility of generating any kind of affirmation in dialogue with the historical proclamations, the questions open up. We chose to keep two of them: which neighbourhood? And how much ours?

Design that was printed on T-shirts and placed as a street poster in front of the Espacio de Todo.

Since the cycle of revolts between 2011 and 2013, we have seen how public space has become an increasingly legislated space where any action, be it political or artistic, is increasingly complex in legal terms. From this arose the strategy that our dialogue with El barrio es nuestro (The neighbourhood is ours) should be seen as a momentary, ephemeral action. Based on a design developed with the questions that emerged from the workshop, we made a series of T-shirts and bags printed manually in silk-screen printing.

We opted for this technique because it is one of the printing techniques that allows the best results and the greatest number of copies in a DIY way. Compared to other fully technical methods of image reproduction, screen printing allows us to control the printing process at all times and to generate our own production circuit without having to outsource it.

︎Opening of the process “A SHOUT ON THE STREET”

On 31 July 2021 we went out dressed in T-shirts and bags printed with the slogan that emerged from the workshop. We instituted ourselves as a space of protest within the public space and liberated part of the textuality of the public sphere from its institutionalised or commodified character so typical of altermodernity. We close this phase of the project in a collective walk that takes us from the Espacio de Todo to the sculpture El barrio es nuestro (The neighbourhood is ours) to invite us, albeit temporarily, to think about whose neighbourhood it is.

You can see the recipe prepared by Elena Blesa for the opening of the process in ︎︎︎Recipes.

*Elena Blesa Cábez (La Sénia, Tarragona, 1988) My name is Elena Blesa Cábez, I am a researcher, artist and mediator. My research focuses on the analysis of strategies adopted by contemporary art to rethink the concept of citizenship today. Situating myself in an intermediate point between pedagogy and artistic production, I work mainly from collective methodologies and dialectical practice.

Since 2018 I am artist in residence at FASE (L'Hospitalet de Llobregat) and coordinator of the education and mediation projects in the Visual Arts programme at Can Felipa. I am part of the assembly of the Institute of Radical Imagination -a transnational work platform that experiments with the crossings between arts and activism from the practice of militant research- and of the Frente Sudaka -a transfeminist and decolonial research/action collective.

Notes

- Marc Suanes Larena, Plantant cara al sistema, sembrant les llavors del canvi: els moviments socials al Tarragonès (1975-2010) (Tarragona: Arola Editors, 2010), 12.

- https://elpais.com/diario/1978/08/02/madrid/270905058_850215.html

- Todo por la Praxis. "Whose neighbourhood is it?", retrieved from: http://todoporlapraxis.es/de-quien-es-el-barrio/

- Elizabeth Lorenzini, Vallekas puerto de mar. Fiesta, identidad de barrio y movimientos sociales (Madrid: Traficantes de sueños, 2007), 40.

- Marc Suanes Larena, Plantant cara al sistema, sembrant les llavors del canvi: els moviments socials al Tarragonès (1975-2010) (Tarragona: Arola Editors, 2010), 12.

- I prefer the use of the word painted to the word graffiti, both because of an emotional and political connection and because I want to focus my attention on the message that they show and not on their aesthetic or artistic value.

- https://www.lavillana.org/

- Sixto Rodríguez Leal, De Vallecas al Valle del Kas. Otra transición (Madrid: Radio Vallecas, 2017), 71.

- Read in the street, Portazgo, 18/07/2021.

- These and other slogans were compiled by TXP together with the Federación de Asociaciones de Vecinos de Madrid (FRAVM) in 2012. Some others were: We want our rights and we want them now / The neighbourhood is ours / Right to a roof / Save the neighbourhood / Solution: fight with the association / Housing here and now / Subsidised housing, speculative housing / Your house is outside / More solutions, less construction / We don't want mud / I also want traffic lights / Our parents emigrated, we didn't, housing here and now / We don't want to live among rubble / We are a piece of the city / The neighbourhood must be fixed.

- Todo por la Praxis. "El barrio es nuestro", retrieved from: https://todoporlapraxis.es/043-el-barrio-es-nuestro/

- Daniel Villegas. "Whose neighbourhood is the neighbourhood?", retrieved from: http://todoporlapraxis.es/de-quien-es-el-barrio/

- Percentage of votes of the first parties by municipality, Madrid Assembly elections 2021. Retrieved from: https://resultados2021.comunidad.madrid/Resultados/Comunidad-de-Madrid/r-1/es

Bibliography

- Rodríguez Leal, Sixto (ed.). De Vallecas al Valle del Kas. Otra transición (second edition). Madrid: Radio Vallecas, 2017.

- Lorenzini, Elizabeth. Vallekas puerto de mar. Fiesta, identidad de barrio y movimientos sociales. Madrid: Traficantes de sueños, 2007.

- Suanes Larena, Marc. Plantant cara al sistema, sembrant les llavors del canvi: els moviments socials al Tarragonès (1975-2010). Tarragona: Arola Editors, 2010.